Pablo Escobar didn’t require expensive advertising campaigns to whet the US appetite for cocaine. The capitalist market economy and the engine of US consumer culture provided Escobar a system that would turn him into a billionaire with influence not only in his native city of Medellin, Colombia but also throughout Latin America. In making Escobar the primary target of the war on drugs, US policy fed his murderous ambition and led to an intensification and escalation of drug-related violence.

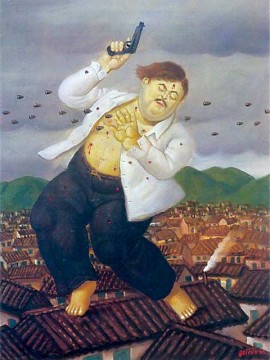

On December 2, 1993, at the age of 44, Escobar was killed in a gun battle with Colombian authorities on the rooftop of one of his hideouts in Medellin, as he and his bodyguards tried to escape. In death the drug lord who built soccer fields in Medellin’s poorest neighborhoods provides the US with a parable of multiple failures.

To this day Escobar is remembered with nostalgia as a heroic symbol to the poor of Medellin. His death did nothing to change the shipping of cocaine to the United States. In fact some scholars, historians and journalists have argued that his death has spread the spoils and corrupting tentacles of the drug trade deeper into Colombian and US society.

Investigative reporters in Colombia and the United States allege that the murderous right-wing paramilitary leader Carlos Castaño has financed his brutal mayhem against thousands of defenseless Colombian peasants with drug trafficking profits. Before becoming the paramilitary commander of the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) Castaño had belonged to a group known as los PEPE’s (People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar). The group was bankrolled by the rival drug cartels of Cali Colombia and it was closely allied with the US Drug Enforcement Agency in its hunt for Escobar. The PEPE’s killed off most of Escobar’s infrastructure in the months leading up to the final showdown. In the vacuum left by Escobar’s death, a broader network of organized crime players entered the power struggle for spoils of the drug war. The PEPE’s were well placed and Castaño profited. In turn this has also drawn the competing leftist guerrilla groups of Colombia into the corrupt web of drug production and trafficking to finance a war that began over social justice.

Investigative reporters in the 1980s wrote about the corrupting influence of an unregulated “wheeler dealer” culture in the US banking system that opened its doors to organized crime and money laundering of drug profits. Today most crime reporting focuses at street level–the war on gangs and on drug-related crime in impoverished urban neighborhoods. Does this focus obscure other criminal activity?

Links:

- Read an excerpt from In Banks We Trust, by Penny Lernoux.

- Report by Amnesty International on alleged US government ties to Colombian paramilitary leaders.

- Reportes de Amnestía Internacional about human rights in Colombia.

- A brief biography of Pablo Escobar and reviews of Killing Pablo by Mark Bowden.