A gang is any group of three or more people who form an organized assemblage and share a common identity. Since publication of Frederic Thrasher’s pioneering study of Chicago gangs in 1927 sociologists have defined the process through which unsupervised youth — especially marginalized youth in urban centers — form street organizations and identities through conflict with authorities and other groups. This classic definition of the street gang includes those groups, which engage in behavior termed delinquent or in conflict with the law.

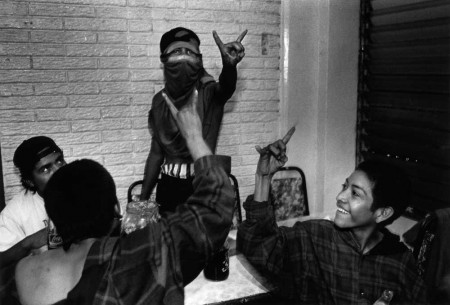

In Guatemala City youngsters who belong to the 18th Street gang "sign" the "E" for Eighteenth Street with their hands. They learned the codes and styles of gang life from deported Eighteenth Street gang members from Los Angeles, California. Copyright © Donna DeCesare, 2001.

For contemporary sociologists like John Hagedorn, an expert on the history of Chicago gangs, global economic forces and the retreat or absence of the State from many communities are factors that promote the institutionalization of groups such as gangs. Hagedorn argues that the failure of neo-liberalism has lead to an intensification of resistance identities among socially excluded youth. But for many developing world youth these contested resistance identities are “supervised” by a variety of criminal groups or religious or nationalist militias.

These insights are relevant to understanding the context and forces shaping the development of so-called transnational gangs like the 18th Street and Mara Salvatrucha. Media portrayals create the impression of organized crime syndicates spreading mafia franchises throughout the US and Central America. The reality is much less formally “organized” or “corporate “ if equally tragic and intolerable.

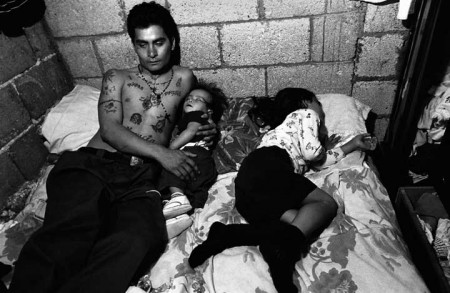

As the stories of the young people profiled in DESTINY’S CHILDREN make clear, the emotional, social, and economic factors, which attract youth to both these gangs, are localized in conditions in the communities from which they come. Gangs provide a sense of something larger to belong to, a sense of shared suffering, identity and resistance to exclusion. Gangs can be ruthless and cruel, but they also provide comfort to fellow gang members– homeboys and homegirls who if they have nothing else at least have each other.

Tattoos and Rituals

Facial and body gang tattoos are simultaneously a defiant assertion of identity confronting exclusion and a source of further exclusion. In the early 1990s most of the gang tattoos I saw—the three dots for La Vida Loca or Crazy Gang Life, or the gang’s name spelled out in letters, numbers or symbols were icons of belonging. And like sailors and soldiers gang members often tattooed the names of mothers or girlfriends and boyfriends as a sign of love and commitment. The tattoos were also a public memorial display for lost homeboys and family members killed in the civil wars of Central America or the gang wars, which followed. In the story titled Jessica: Prisoner of Memories, there is an image of her brother Victor Diaz’s tattoos. There is an aura of a trauma narrative bleeding out his anguished memories onto the surface of his skin.

In the US where tattoos are a socially accepted form of body art, gang tattoos can still be a source of exclusion and barrier to employment. Tattoo removal is one of the ways US gang members transition toward other forms of identity.

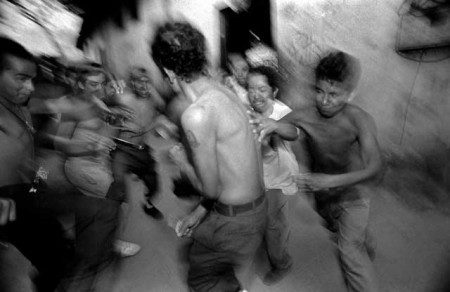

In culturally conservative Central America all tattoos are stigmatized and criminalized. Gang tattoos are not only provocation for conflict among rival groups; they are also a pretext for arbitrary arrest or extrajudicial killing by social cleansing squads. In the first phase of the Mano Duro repressive response, gang identity intensified deepening conflicts with enemy gangs and provoking an increase in both the visibility and violence of tattoo imagery. This is the phase that produced full body or head and face tattoos seen in the most sensationalist media accounts.

At the height of the repression under Super Mano Duro policing policies, the Central American gang response to tattoo removal became a mirror image of society’s intolerant view of tattoos. Removal without permission is considered an act of disrespect and betrayal, a sign that the former gang member may have become an informer. It can carry a death sentence from one’s former homeboys.

Gangs rely on rituals and meetings to enforce codes. Most recently the gangs in Central America have been discouraging tattoos and punishing homeboys who disregard the new rules. Tattoos are now seen as an impediment to the flexibility one needs to move undetected in the informal drug economy. Gangs have always had other identity rituals, gang hand signs, colors or clothing and grooming styles. As gang identities continue to evolve gangs establish new ways of consolidating and expressing identity.

Links: