The United States enacted its first anti-drug law—the San Francisco Opium Den Ordinance in 1875—and adopted an anti-drug stance aimed at Mexico from the early twentieth century. But it was not until the 1970s when US President Nixon established the Drug Enforcement Agency that “war on drugs” became the dominant metaphor for US drug prohibition policy.

It has continued to be a policy followed with varying degrees of transparency and consistency. Documents at the National Security Archives including FBI and DEA reports reveal that there was official US government collaboration with and protection of known traffickers in order to advance the Contra war against Nicaragua. A special Senate subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics, and International Operations, chaired by Senator John Kerry, issued the report Drugs, Law Enforcement and Foreign Policy in 1989. It was first to document U.S. knowledge of, and tolerance for, drug smuggling under the guise of national security. At best the US government looked the other way when the Nicaraguan contras engaged in illegal drugs for arms trafficking to the US.

Critics of US drug policy today argue that the number of illicit drug users in the US—currently 19.9 million—has continued to rise despite the 2.5 trillion dollars it has cost US taxpayers over the last 40 years. The costs are not only in military hardware, enforcement and interdiction programs abroad but also in the expense of a rapidly burgeoning prison system filling US jails with nearly half a million non-violent drug offenders sentenced under mandatory drug sentencing laws. Those opposed to the policy contend that the war on drugs has become a war on public health, on families and on US constitutional rights.

From the 1980s when the US first sought to stem drugs coming from Colombia to US consumers the trade has only become more violent and deadly.

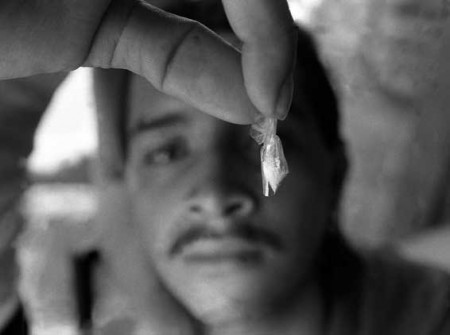

“Spider” holds up a bag of cocaine worth a day and half's wages at the Salvadoran minimum wage. Cocaine addiction is increasingly in Salvadoran shantytowns.

The US characterizes countries like Colombia and Mexico as the source of both drugs and the violence. Mexico counters that much of the violence there comes from sharing a border with a country, which is not only the world’s largest consumer of illegal drugs but also the largest global supplier of illegal weapons.

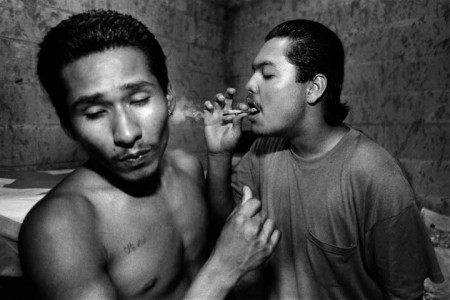

And everywhere it is children and young people who disproportionately suffer the consequences of this “war.” In the exporting countries children in impoverished rural communities may work in the harvesting and processing of drugs. They may be uprooted due to crop eradication policies or wars for control of trade routes that cause human displacement. Some are lured into the drug economy by the promise of economic gain others may be brutalized or forced into the trade by organized criminals.

Refugees displaced by war between paramilitaries and guerillas for control of drug trafficking routes and natural resources and weapons must pass military checkpoints along the river.

And all along the transhipment routes that extend into the vast markets for drugs in the developed world there are children whose families are being destroyed by this war. Whether they are separated from a parent that is a drug war prisoner or have lost a parent to HIV or drug overdose, whether they themselves have been incarcerated for drug possession, the emotional and social suffering of children compounds material suffering.

Critics of the militarized approach argue that a paradigm shift –focusing on public health and harm reduction could stem the ripple effect that is devastating communities. They argue that inclusion of the perspectives of children and young people who are living with the consequences of these policies will provide another way to view the failures of the “drug war.”