The “Cold War” was the name given to the contested relationship that developed between the emerging superpowers — the U.S. and the USSR — after World War II. British writer George Orwell was perhaps the first to use the term. In a 1945 essay “You and the Atomic Bomb,” he referred to living with the shadow of nuclear threat as a permanent “cold war,” which resulted from ideological conflict between the Soviet Union and Western powers.

Abelito holds the remains of a US mortar fragment. The region where he lives near the Honduran border is a hot spot in the counterinsurgency war between Salvadoran government forces and FMLN insurgents.

The US developed a policy of “containment” to prevent the expansion of Soviet power and influence. Both superpowers expressed their conflicting ideologies through the nuclear arms race, espionage, proxy wars, strategic conventional force deployments, and propaganda. Although Soviet expansion into Western Europe had been effectively contained by 1950, the “fear” of encroachment was used to justify the proliferation of the military industrial complex that President Eisenhower warned against as he took leave of office in 1961. It was also used to wage wars on nations that posed no threat to Western European security or to US survival as a superpower.

The human rights consequences of these policies were disastrous in Latin America. Under the guise of combating the “spread of communism” and Soviet encroachment on US territory, the United States supported dictatorships and authoritarian governments with military assistance and training. Operation Condor, a campaign of political repression by right-wing South American regimes employed assassination and intelligence operations to eradicate leftist dissent in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia and Brazil. That the United States participated in a supervisory capacity is evidenced by unclassified documents obtained by Freedom of Information Act and housed at the National Security Archives.

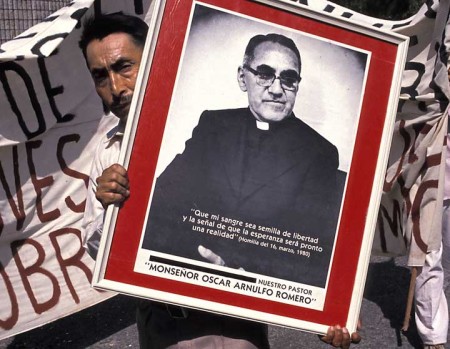

Similar experiences occurred in Central America, where the human rights abuses included the murder of Salvadoran Roman Catholic Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero, an outspoken defender of the rights of the poor. Whether in CIA funded and backed coups as in 1954 in Guatemala or the Contra War against Sandinista Nicaragua, these policies inflamed anti-US feelings in Latin America. In El Salvador and Guatemala in the 1980s when a non-violent opposition movement was met with mass repression, torture and assassination an insurgent response grew.

On the anniversary of the assassination of Archbishop Romero Salvadorans remember the priest who was martyred for defending the rights of the poor.

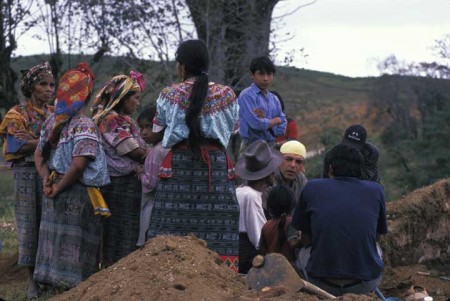

The subsequent counterinsurgency wars in El Salvador and in Guatemala, waged with tacit US support when Congress allowed military aid and with proxy US support through alliances with nations such as Taiwan when Congress cut military aid, provoked partisan debate in the US. The murder of Catholic clergy (bishops, priests and nuns), of trade unionists and members of the popular social movements as well as the mass murder of civilian Mayan villagers –who called for reforms not unlike those for which the US civil rights movement struggled—rendered the Reagan administration’s Latin America policy immoral in the eyes of many US citizens.

Guatemalan Forensic Anthropologists consult with family members of the massacre victims at a site where they are exhuming bones.

With the fall of the Berlin wall and US emergence as the dominant superpower historic injustices did not simply fade. The terrible attacks of September 11th revealed different fault lines in the global system. Although many would argue that the “Global War on Terror” represents a foreign policy shaped by a murky, sub-national terrorist enemy rather than great-power rivalry, the “anti-terrorist” response like the earlier “anti-communist” response is driven by a similarly powerful fear. Such fear in earlier times lead to disproportionate response and the abandonment of values grounded in due process. Equating street gang criminality or drug violence with “the terrorist threat” in official pronouncements does little to explain and much to exacerbate the rush to repressive responses, which undermine the rule of law and deepen impunity. Where this may lead has already been made clear at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo.

On the anniversary of the Jesuit murders people gather at the Salvadoran consulate to protest US policy in El Salvador and to remember the victims --priests, nuns and tens of thousands of Salvadoran civilians-- brutally murdered for defending the poor during the cold war.

The admonition, that an “alert and knowledgeable citizenry” must stand guard against the “disastrous rise” of a military-industrial complex, is as relevant in the 21st century as it was during President Eisenhower’s “cold war” times.